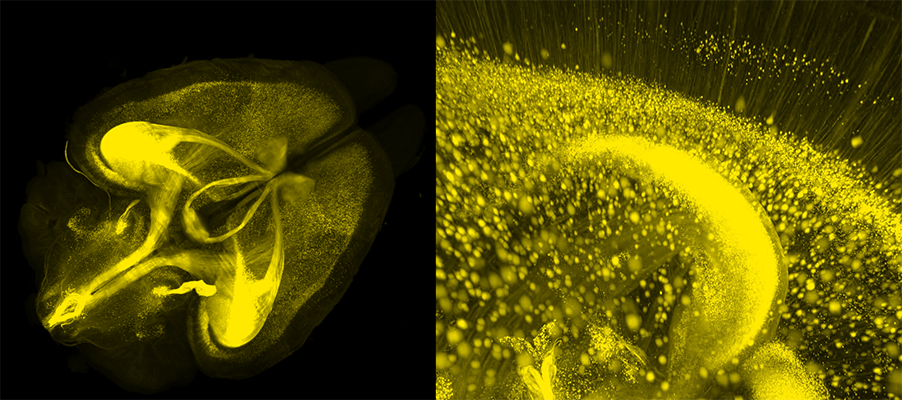

There is a growing trend among biomedical researchers to interrogate biological structures and biomolecular information in three-dimensional volumes rather than in thin slices. This is particularly the case for neuroscientists looking to spatially map the interactions between the hundreds of unique cell types in the mammalian brain. The ability to perform three-dimensional imaging and phenotyping on intact brains will significantly improve our understanding of brain development and various neurodegenerative diseases.

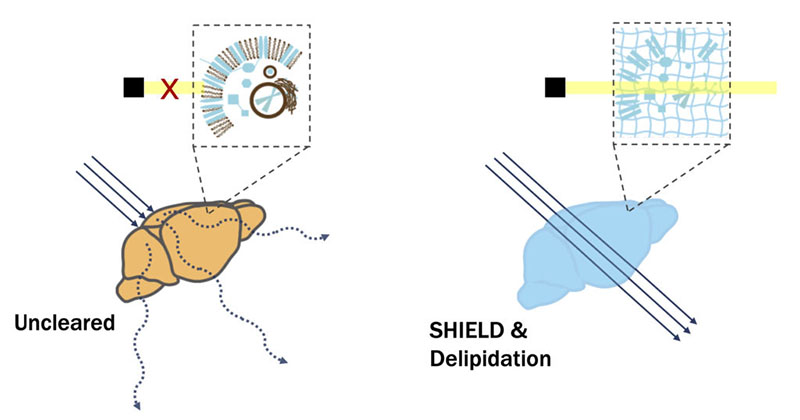

However, inherent light scattering properties of biological specimens present a major challenge for volumetric imaging. Organs, after all, are not transparent. As light passes through tissue, it slows down ever so slightly as it interacts with the multitudes of molecules in its path. This reduction in light velocity is the basis of the refractive index (RI). Importantly, the RI is dependent on both the molecular densities and the distinct physical natures of individual tissue components. For instance, the densely packed lipid molecules in cell membranes can better absorb light than the water molecules in the cytoplasm. As such, lipids have a much higher RI (1.45) than water (1.33). The RI mismatches present not only at this lipid-aqueous interface but also between other tissue components give rise to the light scattering that makes samples opaque.

Tissue clearing methods were developed to address this light scattering problem, thus enabling imaging deep into biological specimens. The first attempt at clearing opaque tissue was published in the early 1900s when Werner Spaltehoz used harsh chemical solvents for removing light scattering tissue components. Although his technique was laborious and resulted in significant tissue damage, it helped further the field of anatomy.

Fast forward one hundred years, the tissue clearing field has been re-invigorated, as researchers have come to realize that reducing light scattering in tissues is critical for unlocking the full potential of powerful modern fluorescence microscopes.

Generally speaking, the goal for all tissue clearing protocols is to render samples optically transparent by homogenizing the RI by removing or modifying some of their components. Because of the significant difference between the lipid and cytoplasm RIs, a common approach is the removal of lipids. To this end, detergents such as sodium dodecyl sulfate are often used in various clearing methods. However, this typically results in the dramatic loss of biomolecular information and structural integrity.

To overcome clearing-induced sample degradation, scientists at LifeCanvas Technologies use the SHIELD tissue preservation system (Park et al., Nature Biotechnology, 2018) to create a reinforced tissue gel that can withstand subsequent tissue processing steps while maintaining protein antigenicity, endogenous fluorescence, RNA transcripts, and native architecture. In effect, this is an evolution of the CLARITY hydrogel technique. ‘SHIELD-ed’ tissue can then be rapidly delipidated using our active clearing device, SmartBatch+, which employs stochastic electrotransport (SE) (Kim, PNAS, 2015) to facilitate the diffusion of clearing reagents throughout samples. The combination of SHIELD preservation and active SE clearing enables the complete and uniform clearing of whole mouse brains in days. And with no tissue damage to boot!